The World Speaks Chinese—Does Your Business?

Nearly 1 in 5 web users speaks Chinese, but less than 2% of internet content is available in Chinese. Here’s how brands can better support Chinese speaking customers.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Share

English is by far the most popular language on the internet: data from W3Techs indicates that 63% of the top 10 million most visited websites are in English. But with 1.3 billion total English speakers—including the 978 million speakers for whom English is a second language—that represents only 17% of the world’s population. This means that nearly two-thirds of the internet is in a language that significantly less than one-third of the world speaks.

Meanwhile, 14.1% of the world speaks Mandarin Chinese either as a first or second language, and Chinese speakers represent 19.4% of internet users. Yet only 1.3% of the top 10 million websites are in Chinese, representing an enormous disparity between speakers and the content available to them (InternetWorldStats).

While a local auto repair shop or a cute downtown boutique may not need its website or customer support team to communicate in Chinese, organizations with a global footprint certainly do. And yet so often we see cases where businesses with Chinese speaking customers don’t offer customer support in Chinese.

Why Chinese Is Hard to Translate

A recurring sentiment we hear is that Chinese is difficult to translate, especially when machine translation is involved. There are a few reasons for this.

Each “word” of Chinese is composed of one or more characters–most often between one and four. There are tens of thousands of different characters, with some sources estimating a total between 50,000 and 100,000. That said, comprehensive modern dictionaries typically list no more than 20,000 characters, while the average educated Chinese speaker generally knows about 8,000 characters (BBC).

When writing a sentence, however, there is no mechanism to indicate a separation between characters, thereby making it challenging to divide sentences into individual words. This is because Chinese grammar is exceptionally simple: in addition to having no spaces between words, the language also does not contain any single/plural forms of words, gendered language, or verb conjugation. In classical Chinese, not even sentences are separated from one another, but modern usage typically denotes a sentence separator with the “。” symbol.

Such stark differences between Chinese and other commonly-used languages on the internet make translating from Chinese to English, for example, far more difficult than the other way around.

As an example, take this sentence in Chinese: “他这个人谁都不相信。”

The literal English translation of this sentence is: “he this person who all no believe.” What the sentence is meant to communicate, however, differs depending on context. But machine translations don’t take context into account, which leads to vastly different translations depending on which engine is used:

Google Translate takes the sentence to mean “no one believed him.”

Meanwhile, DeepL interprets the sentence as “he’s a man who doesn’t trust anyone.”

These two statements have wildly different meanings. It’s not hard to imagine a scenario where an easily misinterpreted translation like this one leads to a massive misunderstanding between a brand and its customer.

Supporting Your Chinese Customer Base

For organizations who currently have Chinese-speaking customers, or those that wish to expand into that market, there are several options for establishing multilingual customer support. An obvious route is to hire support agents to cover each language that your customer base speaks, including Chinese—though this option tends to be far more expensive and time-consuming than many organizations can support.

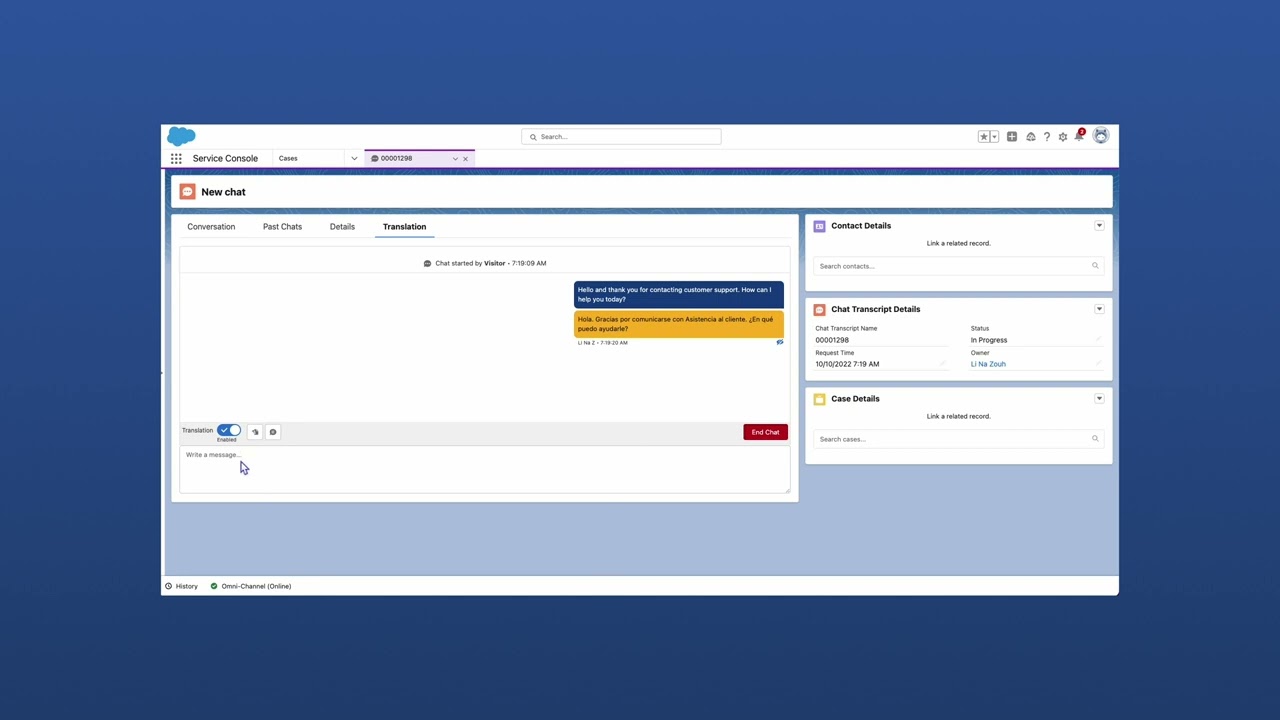

Because of this, the most practical option is to primarily rely upon machine translations to facilitate conversations between your monolingual support agents and Chinese-speaking customers. While machine translation does come with its own set of challenges, here a few ways that you can set up your translations to and from Chinese for success:

- Layer in multiple machine translation engines: Some engines are better at handling certain languages than others. Depending on the language being translated into Chinese or vice versa, Google’s Neural Machine Translation may be the best choice for one translation while DeepL’s may function best for another. In addition to using the best engine for specific translations, having multiple engines allows for the generation of retranslations, in case the first one generated doesn’t seem right.

- Impose a comprehensive glossary to cover slang and jargon: Every industry and business has its own set of terms that need to be handled in a specific way. Think about the word “gross” in the context of a financial firm and how it might differ from that of a pest control company. By imposing a glossary, this tells translation engines how to treat jargon, slang, and acronyms, ensuring that common terms don’t lead to misunderstandings.

- Save human translation for the most important use cases: There will be times that relying on machine translation just doesn’t cut it. If you’re having a sensitive discussion with a Chinese-speaking customer, for example, you don’t want to further complicate matters by sending a translated message when you aren’t one-hundred percent certain of its quality. This is where having an ad hoc human translation resource in place can augment your customer service; it’s reliable and accurate without requiring a constant expense.

Checking those criteria off of a list is the best way to set up your translations for success—including those meant to support your Chinese-speaking customer base.

At Language I/O, our technology incorporates all of these features and more to ensure our customers have the best machine translation tool on the market. Interested in learning more about Language I/O’s solution? Reach out today to speak with a specialist or schedule a demo.